Meet the Author: Physician and Social Worker Sue L. Hall

Josi was born 16 weeks prematurely to immigrants from Mexico who did not know much English. The scrawny infant was blind and had to wear an apnea monitor the size of a small laptop to monitor her breathing.

To Sue Hall, a social worker who became a doctor to help address biological problems that caused later developmental problems in children, Josi could not be saved. So she recommended her parents pull Josi off baby life support.

But her parents, despite their lack of income and English skills, decided to continue care and slowly but surely the little girl began to thrive. Three years later she was attending a school for the blind, walking, and exuberantly singing “Old MacDonald had a Farm” in Hall’s office.

“It was then I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that I had been 100 percent wrong about Josi’s prognosis,” Hall said. “I could not have been happier.”

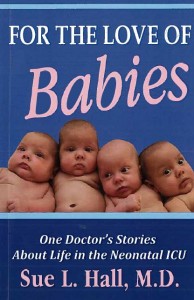

Hall writes about her experiences in the neonatal intensive care unit in “For the Love of Babies” ($8.95 at WorldMakerMedia). SocialWorkersSpeak.org talked to Hall about why she wrote the book, why social workers should read it, and the role of social workers in the healthcare profession:

Q: Why did you decide to write “For the Love of Babies”?

Hall: First, I wanted to honor the strength, courage, devotion, and resilience of the many parents I’ve had the chance to interact with. I have learned so much about life from them. Secondly, I wanted to focus on the emotional aspects of what has become a very technology-driven field. At its core, medicine is about connecting with our patients and recognizing their humanity; sometimes we lose sight of this basic notion. And finally, I wanted to draw attention to the social ills that contribute to our country’s disgraceful performance on measures such as our rates of prematurity and infant mortality, both of which are way too high. I wanted to change the conversation from “Isn’t neonatal intensive care marvelous, the way we save all those babies?” to “What is it about our social systems that leads to our very high rates of prematurity and infant mortality, and how can we go about things differently to achieve better outcomes for all?”

Q: Why do you think this is a good book for social workers to read?

Hall: I think social workers can gain a broad perspective from reading my book: They will be challenged to think about the social determinants of health including the factors creating a high risk pregnancy, the emotional trauma faced by parents whose babies are in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, and some of the ethical issues that the medical team may need to discuss with parents. I think social workers can do their best to support parents of hospitalized infants when they have the big picture in mind, and they can also be quite helpful in interpreting parents’ behavior and responses to medical team members who don’t have the social work perspective. The challenge for social workers is to help parents cope with the enormous stresses they encounter, using their understanding of each parent’s underlying psychological make-up as well as the realities of their social situations. I tried to interweave all these threads into each of the stories. I also believe that social workers are integral and valued members of the hospital team, and I hope I was successful in portraying them in this light.

Q: You mentioned the role of social workers such as “Janice” several times in the book. Do you think the role social workers play in medicine has been largely overlooked, particularly in the entertainment industry that seems to focus more on doing dramas about doctors and nurses?

Hall: The role of social workers has been minimized by the entertainment industry, or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that the entertainment industry doesn’t even have a good handle on how social workers function in a medical setting. The public needs to see social workers as being right there in the middle of things, taking the time to develop relationships with patients and families and to support them through both short-term crises and long-term, complicated hospital stays. Doctors and nurses may breeze in and out of the picture, but it’s the social workers who are often left helping parents make sense of it all once the doctors and nurses have left the room.

Q: What are the biggest challenges you see in the healthcare profession in years ahead? Can social workers help address any of these issues?

Hall: There are several big challenges in healthcare in the coming years. One is that healthcare is hopefully moving more towards preventive care, with interventions to be increasingly focused on the social determinants of health. Social workers need to be active voices in their communities, helping to identify how improving access to jobs, finding safer housing, offering better nutritional choices, and increasing access to care can be accomplished on behalf of their patients and clients. I would also like to see social workers advocate for ensuring that healthcare is delivered in a culturally sensitive manner to all their clients. And, as the push continues to make healthcare delivery increasingly efficient, social workers can perhaps spend time that physicians don’t have, to support patients and families and encourage their follow-through with care plans that doctors prescribe. Social workers can bring attention to the issues of the “whole patient,” broadening the focus from simply the medical aspects of a person’s illness.

Q: Do you plan to write more books?

Hall: I hope to break into fiction with my next book, which is a novel exploring several emotional themes in the context of a medical drama, naturally centered on the topic of babies! In this story, a delivery room disaster rips a family apart, as a woman serving as a surrogate mother to her sister’s baby gives birth. Those left grieving struggle to come to terms with what happened, to resolve their guilt, and to heal their wounded spirits. “Such a Special Gift” is a story of love, of loss, and of gratitude for the gifts we’ve been given.

Dr. Hall earned a bachelors degree in psychology from Stanford University, a masters degree in social work from Boston University, and an M.D. degree from the University of Missouri-Kansas City. She was a practicing social worker before beginning a 25-year career as a neonatologist. She was formerly associate clinical professor of pediatrics at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine and is now in private practice in neonatology in the Midwest.

To learn more about how social workers help clients lead healthier lives visit the National Association of Social Workers’ “Help Starts Here” Health and Wellness Website by clicking here.

| Leave A CommentAdvertisement

1 Comment

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

For eighteen years I practiced social work and taught “behavioral sciences” in the Department of Family Medicine at the Univesity of Kansas School of Medicine. Reading your interview here reminded me of this account that I had journaled some years ago.

Our paths had nearly crossed in anonymity, when she stopped. “Excuse me, but you’re Gary aren’t you?â€

It isn’t an entirely unusual experience. In my work I meet a great of variety individuals: patients, and their families. Charging into their lives on the heels of a chronic illness or traumatic injury, I play my small part of the virtual “Texas Tag Team†flinging diseased organs, cancerous growths and tear soaked tissues out of the ring over the top rope.

“You probably don’t remember me.â€

“No,†I lied, “I do recognize you, but I don’t recall your name.â€

And with a disarmingly warm smile she nods her head, and looks down at the infant in her arms. “It’s OK. Really. We only met once and that was almost four years ago. Dr. O’Neil called you and you came in from home.â€

And the years evaporated. I knew her story in a flash. Every detail was suddenly there. Mike had called me at home at about 9PM on a Friday evening from Labor & Delivery, his voice reflecting an uncommon measure of distress.

We all have our favorite patients or clients or families. And this was such a situation. A young couple, healthy and happy, had successfully struggled to overcome a challenge of infertility. Now in the thirty-eighth week of a cherished pregnancy, the good world of hope and dreams was ripping apart at the seams. Fetal demise, that was the proper term. And in the morning sometime, nature would deliver to the world a new human life. That wasn’t.

I had arrived at the hospital just as the new mornings light was beginning to cast long shadows across the parking lot. Mike met me in his wrinkled blue scrubs and brought me up to date. He’d been up all night and the lost baby had just been delivered. Mom was “OK” and the nurses were right now taking her and her husband back to a private room away from the “mother & baby†unit. That is where I first met this woman who was now standing before me, her and her husband and their newly delivered dream child.

Sadly, it was not an entirely unusual situation and the established compassionate protocol was attentively followed. Off and on for perhaps four hours I sat with the family and their new born son, as they closely examining perfectly formed toes and fingers, the round mottled cheeks, and the soft wavy hair. Perfection gone awry. And at the end of it, all that remains are tiny footprints on paper, a snippet of hair, a Polaroid image, a blue cap, a small blue cotton blanket, and at home an empty crib and freshly painted room. Nothing unusual.

Dredged from the depths of my memory, all the details are there. One family from amongst a crowd of families, and all their tears of suddenly dashed dreams and hopes.

But now I’m looking at this smiling woman standing before me as she shifts her weight to show me the face of the small bundle in her arms. “I saw you, and I immediately remembered you. I had to say something. It’s been four years and it’s Ok if you don’t remember me. It was such a brief time we had together. But I remember you. I remember your kind compassion and your patient guidance when we’d lost direction.

“And I wanted you to know that sad story’s can have happy endings.†Smiling again, “This is our daughter, Cassandra.†And looking down at the small bundle in her arms she softly whispers, “Cassandra, this is Mr. Bachman. He knew your brother.â€

I have been so blessed in my work.

Gary E. Bachman